By Lily Andrews, Environmental Analyst

As carbon-intensive exports face rising border costs, resource-efficient firms are positioned to retain competitiveness and reduce transition risk

As Globalisation has increased, developed markets (DM) are increasingly outsourcing their manufacturing, and the associated emissions, to emerging markets (EM) in a process known as ‘carbon leakage’. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is one of the clearest examples of international trade policy designed to reduce global carbon emissions by addressing this problem and simultaneously ensuring that EU producers are not undercut by their higher emissions competitors.

Introduced in 2023 with a transitional reporting phase, the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will enter its definitive phase in 2026, at which point a financial obligation will apply to imports of steel, cement, aluminium, electricity and certain fertilisers.

For emerging economies, where industrial sectors are more likely to rely on coal-based energy systems and inefficient technologies, CBAM represents both a significant challenge and a potential catalyst for environmental transformation.

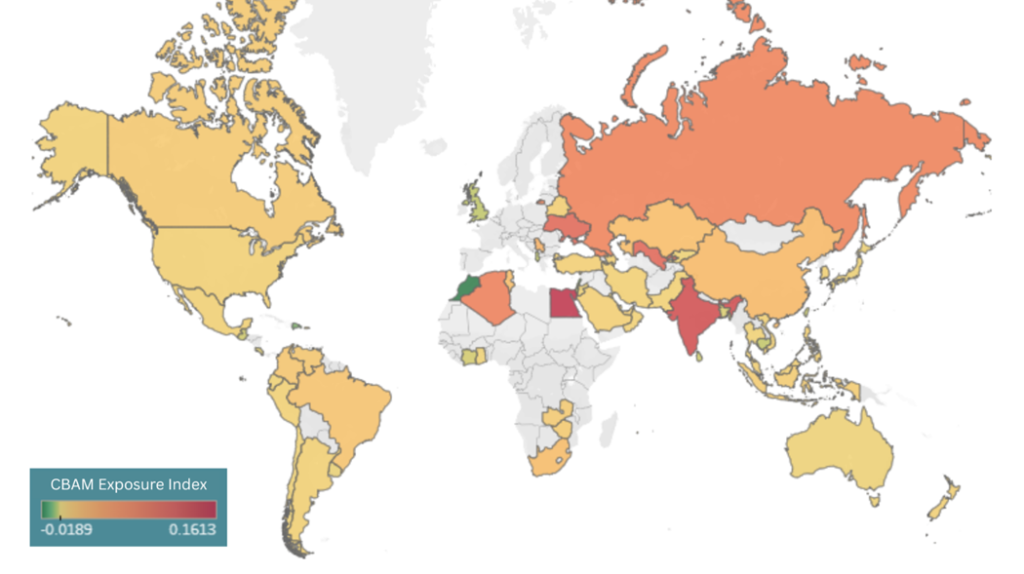

CBAM Trade Exposure Index – Iron & Steel Sector

A Case Study on Indian Steel

Indian steel is especially exposed to CBAM, as the rapidly expanding economy remains heavily dependent on coal-based and resource-intensive manufacturing. India has doubled its steel production over the past decade, and steel now accounts for 12% of India’s national emissions, far above the global average of 8%. This is in part due to roughly half of the country’s production coming from small, unregulated facilities that depend heavily on coal. Further, the low grade of India’s iron ore requires greater energy to process, compounding the issue. The result is an average emissions intensity of roughly 2.5 tons of CO₂ per ton of steel, nearly 50% greater than the EU’s benchmark average of 1.8 tons. With India planning further blast-furnace expansion, the sector could potentially add an estimated 680 million tons of CO₂ equivalent emissions by 2070 unless cleaner technologies, like electric arc furnaces are adopted. At present, these cleaner technologies represent just 13% of India’s steel production capacity compared to the global average of 29%.

Once the mechanism takes full effect in January 2026, importers will need to purchase CBAM certificates, which mirror the weekly average EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) price. These will cover the emissions embedded in products, minus any domestic carbon price. Due to the significant emissions associated with Indian steel production, CBAM will materially raise the cost of exporting steel to Europe.

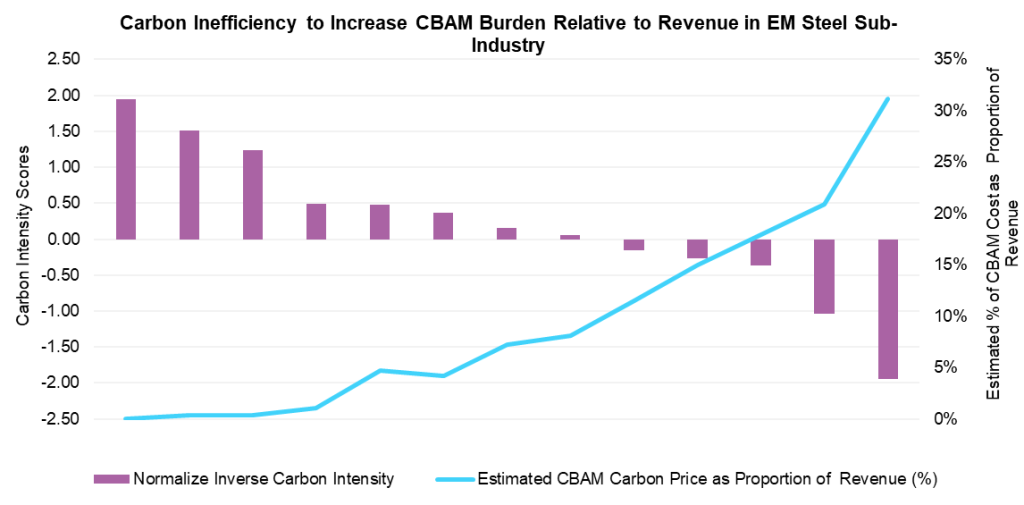

NB: Normalized inverse carbon intensity is a ranking metric using on revenue-based carbon intensities, where higher scores indicate more carbon-efficient companies.

NB: This estimated price is calculated on company reported emissions, an assumed two thirds export share to the EU, an EU ETS price of USD $82, China $12, South Korea $8, Taiwan $9, Turkey $0 and India $0, and assuming all emissions are within the scope of CBAM for these steel producers.

As a result, industry analysts expect India’s steel exports to Europe, which currently comprise roughly two-thirds of its export volume, to decline as the mechanism is phased in.

The chart above compares EM steel producers by their carbon-intensity scores and the estimated CBAM cost as a percentage of revenue. Producers with lower carbon intensity face materially smaller CBAM cost exposure. APL Apollo Tubes Ltd is a clear example. The company’s strong commitment to renewable energy has resulted in some facilities reaching roughly 80% renewable electricity capacity, resulting in low CBAM cost exposure. At the other end of the spectrum, carbon intensity rises toward the right side of the chart, and so does the estimated CBAM burden. The least efficient producers face the steepest impact, with projected costs in some cases exceeding 30% of yearly revenue.

While CBAM is sometimes compared to traditional tariffs, there is a key difference. Traditional tariffs apply the same tax rate to all products within a given category, such as steel, regardless of how they were produced.

In contrast, CBAM differentiates between producers by assessing the emissions embedded in their production processes, thereby prioritising cleaner companies rather than treating all imports uniformly.

The Case for Resource Efficiency

CBAM’s influence extends far beyond trade diversion. Because the policy places an explicit cost on carbon inefficiency, it strengthens the economic rationale for efficiency in emerging regions. Excess carbon emissions are often a direct reflection of wasted energy, outdated machinery, and poor resource management. CBAM therefore rewards firms that are using energy and materials efficiently, have adopted cleaner technologies, and have shifted toward circular production models.

CBAM brings corporate efficiency directly into the cost of goods sold. It moves inefficiency from an indirect effect on corporate profits, to a direct hit.

It is internalising a current climate externality, not with rhetoric, nor with reputational damage, but by using a market-driven mechanism to increase the cost of not efficiently managing resources.

The more efficiently a company is run, the less this mechanism will hurt them.

Potential Outcomes

India is beginning to respond to the announcement of the levy and the government is developing a sectoral roadmap to support decarbonisation of hard-to-abate industries. Other emerging economies are advancing faster. The China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) has deployed new CO₂ based heat-transfer technologies that significantly reduce emissions in a steel plant in Guizhou and is expanding low-carbon power infrastructure for industrial clusters to meet anticipated CBAM requirements.

Still, EM face constraints.

CBAM imposes demanding monitoring, reporting, and verification requirements that many smaller producers are ill-equipped to meet.

Developing countries could also argue that CBAM is a form of “green protectionism,” that disproportionately affects nations that have contributed little to historical emissions and additionally lack affordable pathways to decarbonise heavy industry.

Despite these critiques, CBAM represents a structural and climate-focused shift in global trading.

EM exporters of carbon-intensive goods will face higher costs and competitive pressures in regions adopting border carbon measures. Outside of carbon pricing mechanisms like CBAM, high-emission firms will also risk exclusion from global value chains as buyers increasingly demand low-carbon materials.

Over the short-term, CBAM has the potential to reduce export competitiveness and increase compliance burdens. The longer-term outcomes are far more wide reaching. CBAM has the potential to accelerate EM industrial climate transition, aligning sectors like steel with global efficiency standards and encouraging adoption of cleaner technologies.

Important Information

This document was prepared and issued by Osmosis Investment Research Solutions Limited (“OIRS”). OIRS is an affiliate of Osmosis Investment Management US LLC (regulated in the US by the SEC) and Osmosis Investment Management UK Limited (regulated in the UK by the FCA). OIRS and these affiliated companies are wholly owned by Osmosis (Holdings) Limited (“Osmosis”), a UK-based financial services group. Osmosis has been operating its Model of Resource Efficiency since 2011.

None of the company examples referred to above are intended as a recommendation to buy or sell securities. The company examples are being shown have been selected to be included in this presentation based upon an objective non-performance basis and to provide an example of the MoRE analysis. The company examples may or may not be held in Osmosis’ portfolios as of the date of this presentation. The information does not constitute an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security, commodity or other investment product or investment agreement, or any other contract, agreement, or structure whatsoever.