By Alienor Hammer, Environmental Analyst

No strategy for long-term resilience is complete without considering the ocean. Long overlooked, as the planet’s largest biome, the ocean plays a vital role in regulating climate, supporting global trade, and sustaining biodiversity. Beyond its ecological significance, the ocean is increasingly recognised as a strategic asset – one that can drive innovation, unlock new sources of value, and accelerate the transition to a more sustainable economy.

Key Takeaways

- The ocean is the world’s largest climate asset — it has absorbed more than 25% of human-made emissions, acting as Earth’s biggest carbon sink.

- A tipping point is approaching — ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, and warming seas risk turning the ocean from a carbon sink into a carbon source.

- Financial risk is rising — ocean degradation creates systemic risks for coastal assets, supply chains, and industries from shipping to food, with trillions of dollars in ocean-derived value at stake.

- The blue economy is a growth frontier — sustainable ocean finance offers investors both resilience and opportunity in the transition to a green and blue economy.

Climate Change Mitigation

Our oceans are essential for climate change mitigation. Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, the oceans have absorbed more than 25% of manmade emissions, and are considered the largest carbon sink on our planet[1]. The ocean sequesters carbon in two ways: using a “physical pump” and a “biological pump”[2].

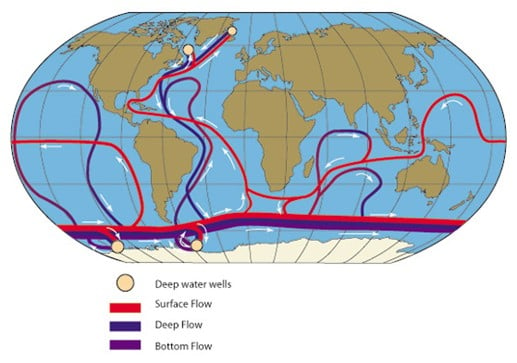

The physical pump uses the Great Ocean Conveyor (GOC) belt, also known as thermohaline circulation, to sequester carbon. The GOC is a system of ocean currents, driven by a difference in seawater density, and controlled by salinity and temperature. The GOC distributes seawater globally and sequesters carbon via deep ocean currents, playing a key role in climate regulation[3]. The physical pump uses these currents, shown in Figure 1: carbon dissolves in seawater, and is carried to the poles, where the water is colder, saltier and therefore denser, thus sinking to the bottom.

The biological pump sequesters carbon by transferring it through the marine food web into deep-sea sediments. Surface and mid-water biodiversity play a central role: organisms accumulate carbon during their lifetimes and, upon death, sink to the seafloor. This process creates a vertical flux of carbon from the ocean’s surface to its depths, locking it away for centuries to millennia.

A key issue of the ocean as a carbon sink is permanence. The physical pump operates on a vast time-scale, with thermohaline circulation taking approximately half a millennium to renew[4], making it relatively resistant to disturbances. The biological pump is also long-term, but depends on ecological integrity and is prone to disturbance. If disturbed, carbon is released, rather than sequestered. As ocean ecosystems undergo global degradation, long-term carbon sequestration becomes jeopardised.

Figure 1. Map of the Great Ocean Conveyor

From sink to source: reaching the tipping point

Until now, the ocean has acted as a powerful buffer against climate change by absorbing vast amounts of carbon dioxide. But signs of strain are emerging. As carbon dissolves into seawater, it triggers chemical reactions that increase acidity, placing immense pressure on marine ecosystems. Organisms with calcium carbonate shells—such as corals, molluscs, and some plankton—are particularly vulnerable, as acidification weakens and can ultimately dissolve their structures.

Marine ecosystems are increasingly at risk from multiple threats, undermining the ecological integrity essential for a well-functioning biological pump. The seas are warming at an alarming pace, with numerous marine heatwaves breaking records this year alone. These changes are severely impacting marine biodiversity, as some species are unable to migrate poleward to escape rising temperatures. The result is population decline and, in some cases, extinction. Corals exemplify this vulnerability: unable to move, they expel their symbiotic zooplankton under thermal stress, leading to bleaching and, when extreme, death.

In addition, fisheries are being overexploited, with trawling devastating entire ecosystems and capturing non-target species in excess. Other pressures include the influx of plastics and microplastics into the ocean, threatening wildlife that become entangled or ingest them, mistaking them for food. The collapse of the Global Plastics Treaty in August 2025 underscores the complexity of addressing these challenges. As action is delayed, anthropogenic pressures continue to intensify. Evidence now suggests this will diminish the ocean’s role as a carbon sink and could even trigger future releases of carbon from this traditionally long-term reservoir, accelerating climate change[5].

The Rising Financial Cost of Ocean Degradation

The ocean is a strategic economic asset worth an estimated USD 24 trillion in goods and services[6]. Aligning economic activity with nature restoration could protect up to USD 5 trillion of this value currently at risk. For investors, ocean degradation presents material financial risks—spanning operational, regulatory, and reputational exposures.

Key sectors such as shipping, seafood, and resource extraction are highly dependent on the ocean and therefore most vulnerable. For example, salmon aquaculture faces recurring public opposition over pollution, while deep-sea mining companies face both financial headwinds and growing backlash. The Metals Company, for instance, reported an $81.9 million pre-tax loss with no guarantee of future returns given regulatory uncertainty and reputational risk. Corporates like Microsoft and Ford have pledged not to source deep-sea minerals, while major financial institutions—including Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, NatWest, and the European Investment Bank—have excluded such projects from financing.

The message for investors is clear: pressure to transition to a sustainable economy is intensifying, and failure to account for ocean-related risks could erode long-term shareholder value.

From Principles to Practice: Capital Flows Into the Ocean Economy

Guidance and principles are emerging to steer the finance sector toward a sustainable blue economy. The UN Global Compact’s Sustainable Ocean Principles, launched this year, provide a framework for responsible practices across ocean industries, building on the Compact’s Ten Principles. Financial institutions are recognised as central players – both in building capacity for ocean-positive growth and in limiting potential harm. Complementary frameworks include the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative’s (UNEP FI) Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles, and World Wildlife Fund’s (WWF) Sustainable Blue Economy Principles.

Concrete action is also underway. Venture capital and private equity are financing innovation directly in ocean-related sectors. Examples include Ocean14Capital, which invests in aquaculture and circular plastics, and Katapult Ocean, a venture fund backing solutions in aquaculture, autonomous underwater vehicles, and shipping. These investments support the transition to a blue economy by reducing plastic pollution, advancing sustainable aquaculture, and improving maritime practices.

Capital is also being raised through Blue Bonds, a subset of Green Bonds dedicated to projects with positive impacts on the ocean. The first was issued by Seychelles in 2018, raising USD 15 million for sustainable marine resource management. Since then, issuances have expanded: in the UK, Tideway raised £250 million via the first sterling Blue Bond to finance London’s “super sewer,” reducing sewage pollution in the Thames Estuary and North Sea, with Lloyds as Global Coordinator. Blue Bonds can be issued by governments, development banks, or corporates, reflecting their growing relevance to both public and private markets.

For broad equity investors, opportunities may appear less direct. A first step is allocating capital to lower-carbon companies, easing pressure on the ocean’s role as a carbon sink—aligned with UNEP FI’s “Protective” principle, which emphasises maintaining the ocean’s core functions. More ocean-specific action must follow, but broad participation is essential. As emphasized at the United Nations Ocean Conference this year, the ocean is critical to the global economy – and the time for finance to act is now.

[1] Uncovering the world’s largest carbon sink—a profile of ocean carbon sinks research | Environmental Science and Pollution Research

[2] The Ocean, a carbon sink – Ocean & Climate Platform

[3] Ocean Circulations | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

[5] Warmer oceans release CO2 faster than thought | New Scientist

[6] Ocean wealth valued at US$24 trillion, but declining fast | WWF

Important Information

This document was prepared and issued by Osmosis Investment Research Solutions Limited (“OIRS”). OIRS is an affiliate of Osmosis Investment Management US LLC (regulated in the US by the SEC) and Osmosis Investment Management UK Limited (regulated in the UK by the FCA). OIRS and these affiliated companies are wholly owned by Osmosis (Holdings) Limited (“Osmosis”), a UK-based financial services group. Osmosis has been operating its Model of Resource Efficiency since 2011.

None of the company examples referred to above are intended as a recommendation to buy or sell securities. The company examples are being shown have been selected to be included in this presentation based upon an objective non-performance basis and to provide an example of the MoRE analysis. The company examples may or may not be held in Osmosis’ portfolios as of the date of this presentation. The information does not constitute an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security, commodity or other investment product or investment agreement, or any other contract, agreement, or structure whatsoever.